- Home

- Dianne Noble

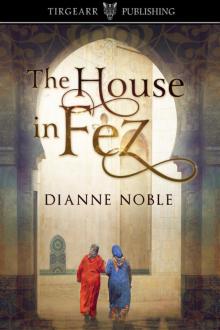

The House in Fez Page 12

The House in Fez Read online

Page 12

‘I think it’s far more likely she wants us to keep an eye on Samir. Make sure he’s not womanising.’ Juliet’s face clouded. ‘You think I’m cynical, don’t you?’

‘Of course not. Well, maybe a bit.’ She fiddled with her watch. ‘Portia?’

‘Mmm?’

‘About me not being pregnant—didn’t you ever want children?’

In the pause, a moth bumbled into the candle flame and there was a hiss.

‘Of course. But it just never happened. I had all the tests.’ She swung her legs over the side of the bed. ‘Be truthful, Jules, what sort of a mother would I have made? Given my… habit?’ She thrust her arms in front of Juliet, the recent scars still livid.

‘Oh, Portia…’

‘Anyway, I don’t want to talk about it. Any of it.’ She turned away. ‘Is Darren okay with you staying longer? Did you phone him?’

‘He’s happy I’m feeling better here. Says stay as long as I can. What about Gavin? Did you text him?’

‘No. He wouldn’t bother answering anyway. He thinks I’ll always be around to fall back on—a bit like the emergency services.’

Juliet

She didn’t know what woke her. She crept to the window and removed the folded piece of cardboard which kept the shutters closed and looked down into the courtyard where, silhouetted by the light from the lamp over the outside door, Miranda was dragging her suitcase, its wheels juddering on the tiles. Juliet watched her go through the door with Samir, both of them swallowed up by the darkness of the medina.

How does she feel about putting her house at risk? Is she frightened? And is it hard for her to go and leave her new husband with his first wife?

She lay awake for a long time, her mind a jumble of thoughts about her mother. Would everything turn out all right? Would Samir treat her well?

Not until the dawn prayers began did she finally slide into the soft, dark warm of sleep.

As she came out of the bedroom birds were singing, and she stood for a moment enjoying the early morning cool. Zina emerged from the room next door, pulling a sleepy-looking Hasan by the hand.

‘Good morning,’ Juliet said, grinning at the yawning child.

‘Marhaba,’ Zina said.

‘What does that mean?’

‘Good morning also.’

‘Marhaba then. And marhaba, Hasan.’

He gave her a shy smile. He was smartly dressed in grey trousers and a white shirt, with a tiny backpack.

‘Are you going to school?’ Juliet squatted in front of him and looked into his solemn brown eyes. He glanced up at his mother and didn’t answer.

‘Can I give him a sweet?’ Juliet asked, fishing in her pocket for a Murray Mint.

Zina nodded and Hasan took it, unwrapped it and gave the paper to his mother.

‘You come,’ she said to Juliet.

‘To the school?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’d love to. Thank you.’

Zina closed the bedroom door and Juliet wondered if Samir would share her room every night now, until Miranda returned. And how did it work? Did he keep half of his clothes in each room? And were there two wash bags?

A mist like damp muslin hung over the medina as she followed Zina and Hasan through the alleys. As they pressed back against a wall to let a drove of donkeys clatter past, Hasan looked up at her with his liquid eyes and she smiled at him. ‘He is a beautiful child, Zina.’

She nodded. ‘Thank you. Shukran.’

She understands most of what I say. Maybe she’s found it useful to look blank around the others. Good for her.

It didn’t look anything like a school, just an ancient stone building with a blue door where paint had run and set in drips as if it were rain. Children, mostly boys—why didn’t that surprise her?—milled around the entrance. All were clean and tidy with a freshly-washed look and rucksacks strapped to their shoulders.

Zina bent to speak to Hasan. His lips parted and she removed the remains of the Murray Mint and put it in her own mouth. She kissed his cheek, then gave him a gentle push. At the door he turned and waved. He looked heartbreakingly small.

‘Come,’ Zina said, putting a hand on Juliet’s arm. ‘We buy food.’

Juliet followed her through a warren of subterranean passages, occasional lamps casting the only light. On either side of them the walls were black and reeking, the thick air smelling of stale urine and putrefaction. She shivered. Imagine getting lost here. As they came out into dazzling light she had to stand still for a moment, shielding her face from the sun with her hand. When her eyes stopped watering she saw a tall tree, clamped to the ground by up-torn tiles and beneath it a riot of colour. On all sides, laid out on sheets, were mounds of scarlet tomatoes, lemons, vivid green beans, and creamy white cauliflowers.

Zina tested the vegetables—pressed, prodded and smelled them before passing them to a woman in a dark blue djellaba and white headscarf who dropped them onto the tray before adding weights to the other side of the scales. Her hands were calloused, the nails broken, and she darted quick looks at Juliet as she took the money, then tipped the food into Zina’s capacious cloth bag. Next, they pushed their way to a stall selling glistening olives.

‘For tagine,’ Zina said.

‘I love tagine.’ Her mouth watered at the sharp smell.

‘I also.’ Zina’s eyes sparkled. ‘Too much. Get fat.’

On impulse, Juliet hugged her. ‘I’m so glad you’re here. I do hope we can be friends.’

Zina’s brow furrowed. ‘Shwayya. Slow, speak slow.’

‘Friend. You, me, friend.’

‘Ah, friend. Aiwa.’

‘What is aiwa?’

‘Is yes.’

As they walked home, the sweet smell of herbs trampled underfoot by the donkeys filled the air and shafts of sunlight angled down into the lanes. Juliet’s heart was full. I’m happy. I have two friends now, my sister and Zina. Maybe she had been suffering from depression—understandable given their precarious financial position and the trauma of Jacob’s disappearance. Her throat tightened as she thought of her son, but after a few minutes it eased. Being here, one step removed, seemed to make it more bearable.

They arrived outside the riad at the same time as Samir.

‘Marhaba,’ Juliet said. ‘We’ve been to the market and it was just brilliant. You have been shopping too?’

Raising an eyebrow, he said, ‘Shopping is work for women.’ He waited until Zina had edged past him through the door before leaning back against the wall and letting out a long breath. ‘I have been searching for labourers to clear away the fallen ceiling. In four days it is Ramadan. Nobody will wish to do heavy work then.’

‘I don’t suppose you can blame them.’ She clutched his arm. ‘Look at her,’ she said in a low voice, pointing to a tiny girl in a torn dress sweeping the steps of the house opposite. Her thin body was bursting with sores and dirt caked her bare feet.

‘Come away.’

‘Why?’ She looked up into his face, saw sadness there.

‘She is a servant of my neighbour.’

‘She is a child.’

‘Oh, Juliet, you are not in England now.’ He sighed. ‘I know this is shocking to you, but there are many like her.’

‘But why?’

‘They are brought here from the countryside. Their parents are unable—or unwilling—to feed them.’

Tears slid down Juliet’s face, dripping onto her shirt, making dark splodges on the pale blue cotton.

‘Juliet,’ he said softly, ‘it is not good to care so much. Come inside. Please.’ He took her hand and urged her through the door. As it banged shut behind them, she buried her face in her hands.

Portia

Portia’s heart lifted to see Gavin’s text asking when she would be coming home. Perhaps all was not lost. Perhaps he missed her—or had he run out of clean shirts? It seemed the most likely explanation. She sent a breezy reply informing him she had absolutely no idea when she would return. Let him m

ull that one over.

In the courtyard, Juliet and Zina sat close together in the shade of the tree, shelling peas. They laughed, seeming comfortable together, and a twinge of envy pierced her. It reminded her of netball at school when lines were drawn, teams picked and she hadn’t been included.

‘Hello.’ Juliet squinted into the sun as she smiled up at her sister. ‘Want to join us?’

‘No, thanks. I’m going out.’

Juliet’s smile faltered. ‘You’re not going… don’t—’

‘I won’t.’ Portia gave her a broad grin. ‘Where’s the old witch this morning?’

‘In the salon, out of the sun. I think I should warn you that Zina knows more English than she lets on.’

Portia gave Zina a curious look. ‘Interesting. Still, I doubt she’s any more fond of ma-in-law than we are, so I’m sure we can speak freely.’

Juliet popped another pod. ‘What d’you think Miranda will do about her house?’

‘Flog it if there’s not long to run on the tenancy agreement.’

She shook her head sadly. ‘I’m off now. Need anything?’

‘No, we went shopping earlier.’

She felt Juliet’s eyes on her all the way to the door, and turned back. ‘You worry too much, Jules.’

‘Can’t help it.’

In the medina she asked a young boy in shorts and a T-shirt—who should have been at school, in her view—to take her to the Banque Populaire and wait until she came out again. How much easier life had become since her discovery that so many people here spoke French. Not that hers was great—she’d failed the subject abysmally at school—but it was definitely better than her Arabic.

Her sunny mood evaporated as she stood in a long line at the bank, only for the cashier to close his window just as she reached the front. People around her shuffled and muttered as they formed a new line. A man with a mouthful of rotting teeth fixed her with an unblinking stare, and a fat woman with the musty smell of old perfume and stale armpit tried to barge in. Portia glowered at her and moved closer than she would have chosen to the man in front in an attempt—futile as it turned out—to block her way. Sweat trickled down her back as she gazed at the armed policeman at the door and then at the portrait of the Moroccan king. Pictures of him appeared in every shop in Fez because, Miranda said, he was directly descended from the Prophet.

At long last she reached the head of the queue, but trying to make the teller understand she wanted twenty-six fifty-dirham notes almost tipped her over the edge. How hard can it be? It’s under a hundred quid, he’s got my bank card, what is his problem? Tempted though she felt to drag him over the counter by his officious collar, she stayed calm and repeated her request yet again. This time he understood, and complied.

At last. She snatched up the notes, stuffed them in her bag and raced out.

‘Maintenant…’ she said.

The boy jumped to his feet and looked at her expectantly.

‘La Musee Nejjarine, s’il vous plait.’

He shook his head.

Must be my crap accent.

She tried again, more slowly, and watched realisation dawn on his grubby face. He trotted ahead of her, looking back often to make sure she kept up.

The hinges of the sweatshop door squealed in protest as she pushed it open. Heat, and the smell of stale air hit her as the children looked up.

‘Bonjour,’ she said.

They giggled and nudged each other.

‘Francais? Parlez-vous Francais?’

Faces brightened and a boy in a red shirt rattled off a volley of sentences.

‘Er… je parle Francais un peu,’ she said, showing them with her finger and thumb just how limited her grasp of the language was.

The boy spoke again, more slowly, but she still couldn’t understand a word he said. She reached into her bag and brought out the bundle of notes. They watched in total silence as she peeled off one for each of them, and stared at the money that was pressed into their hands, some looking confused, others delighted. Then the buzz of excited chatter filled the air and she shot a worried look towards the door. If Samir were to turn up, if the children fell behind with their work… She wondered what the French was for ‘don’t stop stitching’ and cast around in the marshy recesses of her brain, emerging triumphant.

‘Travaillez.’

At once they tucked away their bank notes—in pockets and up knicker legs—then picked up their slippers. She could have cried. What difference could fifty dirhams—less than four pounds—make to their miserable lives? Would they buy food with it, or would they take it home for the family? She edged around them, then lifted the lid of the water container and looked inside. It was almost full and seemed to be clean. Then she caught sight of dusty blankets in a corner, next to a metal bucket. Surely it couldn’t be someone’s bed?

‘Pardon.’

They all looked up. Pointing, she said, ‘Est-ce que… er… personne dormez… ici?’

Nobody replied. She put her hands together and mimed sleep. Several children exchanged glances. How could she make them understand? As she tried to think of another way to ask, a girl stood up. Small—only reaching mid-thigh on Portia—she had matted hair, and legs which were dark with dirt. She pushed past the others and lay down on the blankets, looking up at Portia.

‘Vous dormez ici?’ Portia whispered.

She nodded, then scrambled to her feet and went back to the others while Portia stared at the filthy rags in horror. Why did she sleep here? Did she have no family? Did she have to use the bucket as a toilet in the night?

There has to be some way I can help her—all of them—but her particularly.

Back at the riad, she stormed into the kitchen where Juliet and Zina were chopping carrots. ‘Where is Samir?’ she asked.

‘He’s out looking for labourers. Why, what’s the matter? You look… angry.’

‘I am bloody angry,’ she snapped. ‘It appears one of Samir’s little workers—slaves—has to sleep in the sweatshop.’

‘I wish you wouldn’t, Portia,’ Juliet said, putting a hand on her arm.

She threw it off. ‘Wouldn’t what?’

‘Rock the boat.’

‘Rock it? I’ll capsize the bastard thing.’

As Portia crossed the courtyard that evening, stars punctured the black sky and the smell of roasting meat wafted in from the medina. Zina came through the door from the salon, chivvying Hasan towards the stairs.

‘Is it his bedtime?’ Portia asked.

Zina gave her a blank look.

‘Sleep? Bed?’

She nodded and rushed away. Portia watched her go. It seemed the friendliness only extended as far as Juliet.

In the TV room, Samir and Juliet were watching the news, blue light from the ancient screen flickering over their faces. Lalla lounged on the sofa with her feet up, cracking nuts. When she caught Portia’s look she stopped chewing and stared at her with dark, expressionless eyes. Portia gave an elaborate yawn and then, when nobody seemed to notice, another one. ‘I’m whacked,’ she said. ‘I think I’ll call it a day.’

The medina door had been locked for the night. With infinite care, Portia slid the first bolt back a centimetre at a time, wincing as it grated. She held her breath and waited a moment, but nobody appeared. She eased the second one along gently and, with a last look over her shoulder, slipped out into the lane. Beside a low wall, a cooking fire crackled, sparks shooting up into the night sky like tracer fire.

The alleys were dark and silent. Scavenging cats slunk by her and a woman carrying a covered dish stared at her as she hurried past. On the corner stood a man wearing a woollen hooded cloak. As she drew alongside him she glanced up and was chilled by his dead eyes, beaked nose, and gaunt cheekbones. She rushed past him, then stopped. You don’t know where you are after this bit. Stand still. Wait until someone comes by to ask. Hiding in the darkness, by the wall where it was thickest, she waited, hoping a young lad would walk by but only two women pas

sed, whispering to each other, and then an old man, bent over his stick. This is hopeless. I’ll have to give up.

As she turned back a boy cannoned into her and she grabbed his arm. He tried to pull away, but she kept hold. ‘S’il vous plait—la Musee Nejjarine?’ She fumbled in her bag for money and he nodded.

He sped through the network of alleys and, breathless, she struggled to keep up. Broken stones were lumpy under her feet and she tripped more than once. It seemed like no time at all before they arrived: a journey which took an inordinate time in the day was simplicity itself when the lanes had emptied.

She turned the door handle, then turned it the other way. Finally, she rattled it for good measure. ‘Bonjour,’ she called, hammering on the door. ‘Bonjour.’

A little, piping voice replied, ‘Bonjour.’

‘Can you open the door? Er—ouvrez la porte?’

Silence.

‘Ouvrez?’

‘Non.’ And then came a whole jumble of words she couldn’t understand.

Helplessly, she stared at the door, tried the handle again, then sagged against the frame. He’d locked her in. The bastard had locked her in. What if there were an emergency? What if a fire broke out? Fury rose in her throat like bile. Tears of frustration scalded her eyes as she tried one last time. No good. It wouldn’t open.

The boy had gone. Why would he do that when she hadn’t paid him? She peered into the darkness, but there was no sign of him. Shit, could this night get any worse? She set out in what she hoped was the right direction, but when she saw darting shadows by her feet—cats? rats?—doubled back. Now nothing looked familiar. Leaning against a wall, feeling brief comfort from the day’s warmth stored in the stones, she took a few long breaths. Chill. Look around before you move. Maybe… Above her, spectral washing was charcoaled against the night sky. Along the lane, light suddenly spilled from a window, then was cancelled out as someone closed the shutter.

‘Hello?’ she called. ‘Hello?’ The darkness absorbed her voice. She started walking again through tangled alleys, passed houses packed tight as teeth, met nobody. A cloud of mosquitoes fizzed around her head and a dog, lying in an inky pool of shadow, snarled at her. She broke into a run, tripped on the grid of a water channel, and crashed to her knees. As she hauled herself to her feet, a man loomed in front of her, held out a hand. She raced away, kept running until the stitch stabbing her side made her stop. Hands on her thighs, she bent double and gasped for breath. When she straightened up, she saw a line of empty market carts tipped up against a wall and knew she was hopelessly lost.

The House in Fez

The House in Fez